“You are simpler than Microsoft Word”

In this edition of the Weekender: The Classics Strike Back, a requiem for a tree, and a guide to smørrebrød

This week, we’re mourning a tree, struggling to spell smørrebrød, and revisiting Middlemarch.

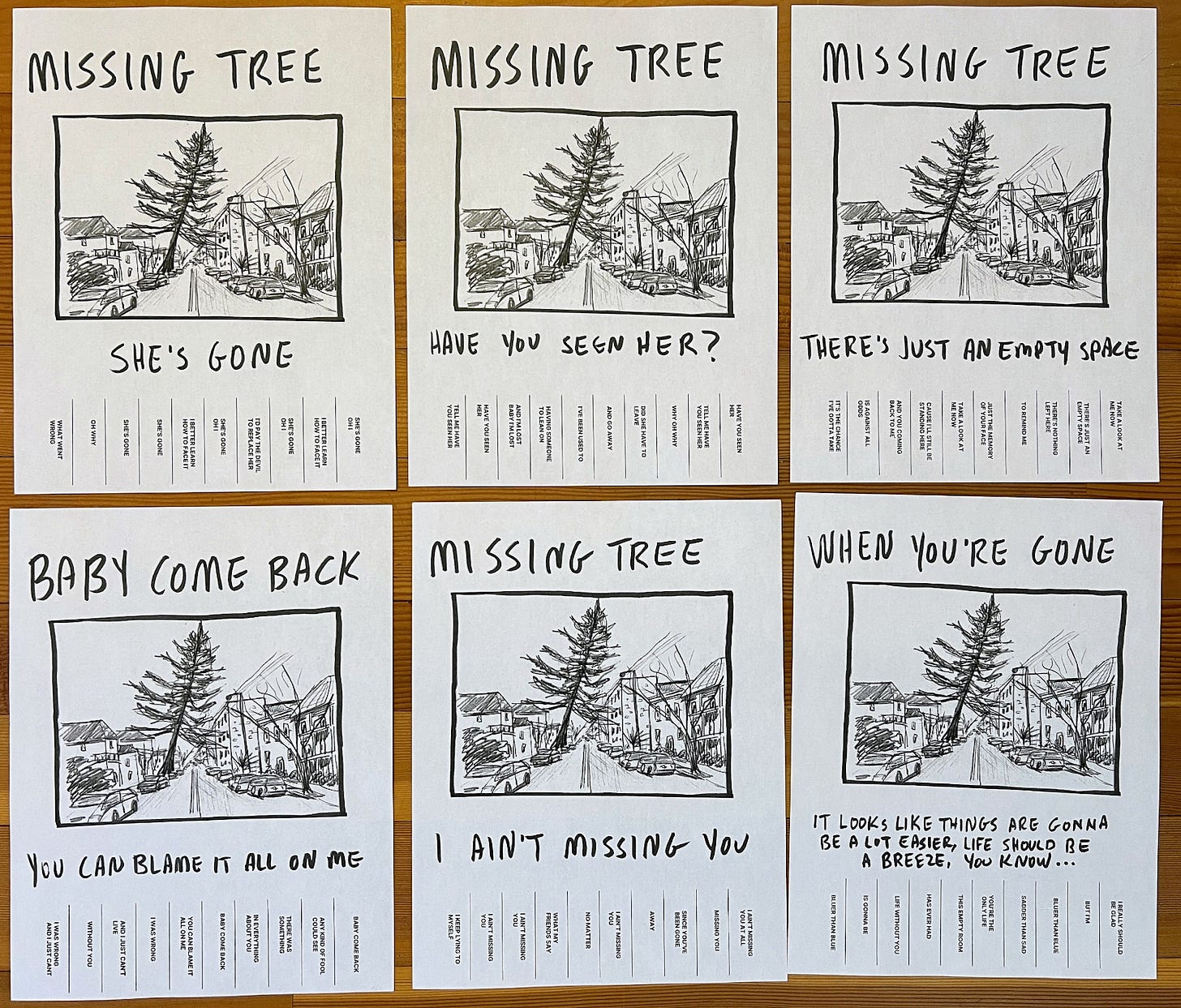

NATURE

Requiem for a tree

This ode to the loss of a neighborhood tree explores how art and community can help us navigate the little griefs of life.

Requiem for a tree

—

inAt first I didn’t even like the tree. It blocked my view.

It wasn’t a special or important tree. A deodar cedar, or Himalayan cedar, is a common tree in Portland and just about everywhere else. But it was big, which meant that it was old, which made it impressive.

It didn’t take long for me to understand that it wasn’t blocking my view. It was my view.

Its cones were white, and they stood straight up and glowed against the deep shadowy branches. The first time I saw those cones emerge, I thought the tree had been visited by a flock of white birds.

The best view of the tree was from my bedroom window. I would look out at it when I couldn’t sleep. That’s what I’ll miss the most, waking up in the middle of the night and seeing it loom over the rooftops against a dark sky, and imagining that it is full of sleeping birds.

[...]

I’m not surprised that it had to be cut down. It leaned precariously across the street. Not one but two apartment buildings stood directly in its path. It didn’t belong in a little sidewalk strip, it belonged in a forest.

Which this neighborhood once was. From its perspective, we were the ones in the wrong place.

But here we are.

When a red ribbon appeared around the tree, with a notice attached to it announcing the end of its life, my heart ached for it.

“Poor doomed tree,” I said to my husband as we walked by and read the notice. “I bet it doesn’t know why it has a ribbon around it.”

“It probably thinks it’s getting a plaque,” he said.

Oh, that crushed me! Of course it would’ve hoped for a plaque! Over the roofs of the apartment buildings across the street, it could see the tops of two venerable old elms that both have plaques. It had been watching those elms since before I was born.

What do they have, the cedar might’ve wondered, that I don’t have?

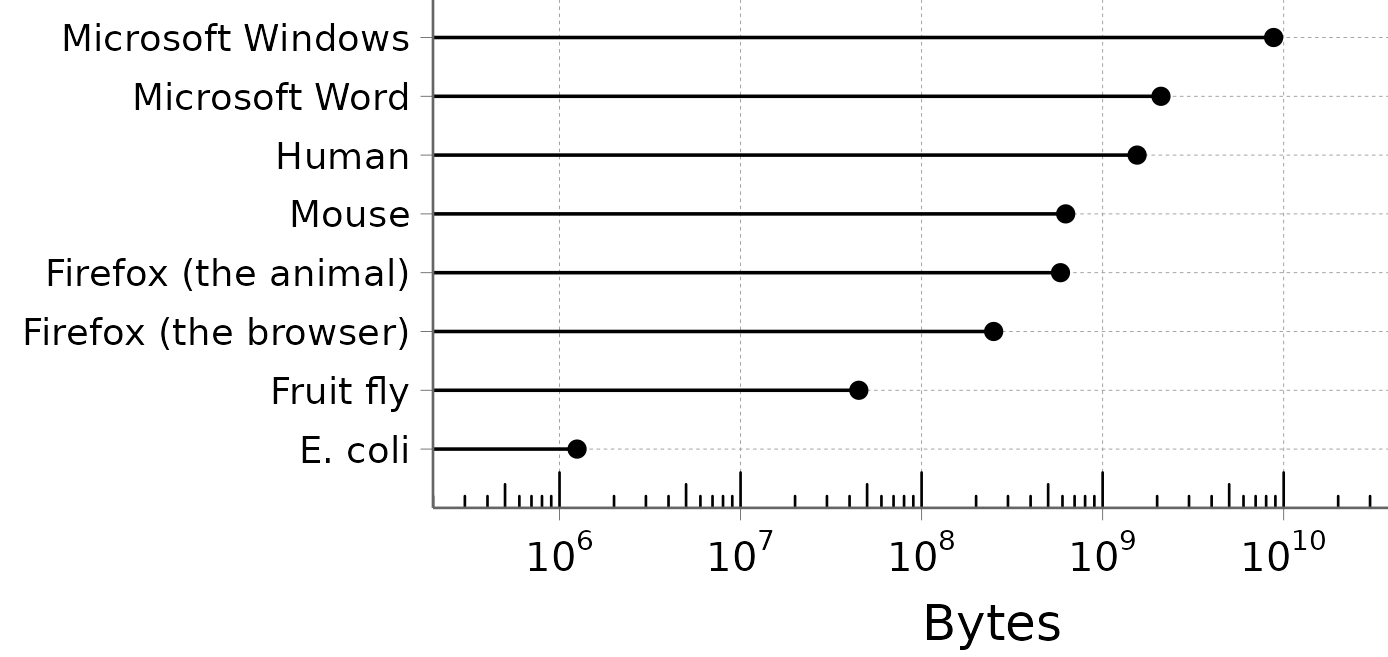

SCIENCE

“You are simpler than Microsoft Word”

In the midst of a big week for AI news, Malmesbury argues that humans are already great at building incredibly “complex” things—but nature still has us beat when it comes to designs of elegant simplicity.

Mechanisms too simple for humans to design

—

inBy “complexity,” I mean complexity in the Kolmogorov sense: how much information you need to completely describe something. This definition is particularly convenient for two things: software, and living organisms.

For example, the Tetris game fits in a 6.5 KB file, so the Kolmogorov complexity of Tetris is at most 6.5 KB. It’s a pretty simple system. In contrast, the complete Microsoft Word™ software is a much more complicated object, as it takes 2.1 GB to store.

We can do the same with living organisms. The human genome contains about 6.2 billion nucleotides. Since there are 4 nucleotides (A, T, G, C), we need two bits for each of them, and since there are 8 bits in a byte, that gives us around 1.55 GB of data.

In other words, all the information that controls the shape of your face, your bones, your organs and every single enzyme inside them—all of that takes less storage space than Microsoft Word™.

We can go further: only 10% of the human genome is actually useful, in the sense that it’s maintained by natural selection. The remaining 90% just seems to be randomly drifting with no noticeable consequences. That brings your complexity down to 155 MB—not even a CD-ROM worth of data.

(There’s an open debate about whether genomes really contain all information needed to describe a species—since each cell is built from another cell, there might be additional information in physical cell structures. My guess is that, since this non-DNA information is not a substrate of evolution the way DNA is, it likely doesn’t contribute significantly to overall complexity.)

I like the organism/software comparison, because it goes to show how insanely compressed living organisms are compared to human-made software.

PHOTOGRAPHY

POETRY

How to read a poem

Lynn Steger Strong shares a beautifully accessible approach to poetry.

Bounce, Bounce, Shush, Shush

—

inA thousand years ago, while in graduate school (and, for good measure, eight months pregnant), I taught in a summer program that offered high school students a broad range of readings, writing, a compendium of the program where I went. The kids were sweet and earnest, many of them talented, invested in the things they wrote and read. It was one of the only times I was tasked with teaching poetry, and I felt in over my head. Like visual art, I know when a poem holds me, grabs me, I know when my eyes just skim the surface of it. But I have no language for the how or why of it. A poet friend had just moved out of the city but was back for a few weeks and was sleeping on our couch. She was also, in the vein of poets being often lovely, generous, cooking for me almost every night she stayed with us (my husband was out of town, and before she got there, I’d been living off takeout French fries and Indian). I asked her how to introduce poetry to these anxious earnest kids. Tell them it’s pre-writing, she told me, pre-literacy. Tell them its origins are in shaping language so sticky that it can be passed on (I’m not quoting, obviously; sticky is my word, but this is the heart of what she said; it’s what I still think of all the time when I think of her, sitting on our couch eating the delicious vegetarian curry that she’d cooked us, baby kicking, whirling as we did). She told me its origins are in the simple but essential need to communicate, to keep safe and also to feel intimacy, understanding, to (and this is E.M. Forster) connect: I thought immediately of the rhymes we learned about the different snakes to be afraid of in the swamps behind our house when we were kids. About all the books that since then I carried with me: rhythms so intractable that they still knock around in my brain, in my toes, my belly—not unlike that kicking baby—long after they’ve been read.

ILLUSTRATION

STORYTELLING

LITERATURE

The classics

You’re not imagining it: everyone really is reading Middlemarch. Petya K. Grady investigates the trend, and what our renewed interest in the classics says about the cultural moment.

Why is everybody reading Middlemarch right now?

—

inThere’s something almost rebellious about choosing to read Middlemarch in an era of endless scrolling. George Eliot’s careful examination of provincial life, with its intricate web of human relationships and moral choices, couldn’t be further from the quick-hit content that dominates most of our media diet. When you commit to reading War and Peace, you’re not just reading a book—you’re making a statement about what kind of relationship you want to have with culture and with your own attention.

This return to classics isn’t about cultural snobbery or performative intellectualism. Instead, it seems to represent a genuine hunger for works that demand something of us—books that ask us to sit still, to think deeply, to engage with complex characters and ideas over hundreds of pages. These novels, written during another time of massive social transformation, offer us something our current media landscape rarely does: the space to sit with complexity, to understand characters whose actions we might disagree with, to see how individual choices ripple through entire communities.

Perhaps what we’re really seeing is the emergence of a new kind of digital literacy—one that doesn’t just mean knowing how to use platforms and navigate algorithms, but also knowing how to use these tools to nurture your own deeper intellectual and creative needs. When we read Anna Karenina or Middlemarch on Substack, sharing our thoughts and experiences with others, we’re not just reading old books in a new format. We’re actively reshaping what it means to be a reader—and a human—in the digital age.

So yes, just like everyone, I am trying to read the big classics right now—started Anna Karenina earlier this week and, like Lincoln Michel, finding it weirder, hornier, and funnier than I’d expected (my January Reads post will be up on Sunday). But more than that, it feels to me that I am figuring out how to read in a way that matters to me, using modern frameworks that engage with these works in ways that enrich rather than diminish my experience. I am finding that doing so is starting to reveal a path toward a more sustainable life online, and in a weird way it feels like I am not just reading a novel, I am learning how to pay attention again. In an age of infinite distraction, that might be the most radical act of all.

STILL LIFE

FOOD

Smørrebrød

This guide to smørrebrød, a Danish classic “served across all strata of society, from extremely fancy restaurants to working-class lunch counters,” answers the all-important question: Does avocado toast count? (No.)

How to Make and Eat Smørrebrød

—

inWhile an open-faced sandwich might not seem all that exciting to the uninitiated, Danes have made it an art form. In the nineteenth century, the onset of industrialization meant that factory workers couldn’t return home for lunch, and they needed something portable and hearty that could last until midday. Butter (or goose fat) spread on rye bread ensured that whatever meat or fish (usually left over from dinner the night before) got heaped on top wouldn’t seep through and make the bread soggy.

Some aspects of the original remain to this day. Smørrebrød literally means “butter bread,” and butter is still smeared on a slice of bread from crust to crust before other toppings get added. Nowadays, in addition to fish, cold cuts, and sliced cheese, various spreads and garnishes, such as potato salad, hummus, microgreens, veggie chips, and other contemporary toppings, might find their way onto a beautiful smørrebrød. Entire restaurants are devoted to these open-faced sandwiches, where extraordinary care is given to layering the components on smørrebrød in a way that is as visually pleasing as it is delicious.

GHOSTS

Substackers featured in this edition

Art & Photography:

, , , , ,Video & Audio:

Writing:

, , , ,Recently launched

Inspired by the writers featured in the Weekender? Creating your own Substack is just a few clicks away:

The Weekender is a weekly roundup of writing, ideas, art, audio, and video from the world of Substack. Posts are recommended by staff and readers, and curated and edited by Alex Posey out of Substack’s headquarters in San Francisco.

Got a Substack post to recommend? Tell us about it in the comments.

Obviously, it would be more accurate to say my genes are simpler than Microsoft Word. The basic code for my physical body, in other words. But that's not ME. That's not the sum total of all that I am, as an individual. There's a lot more complexity to what makes me truly me than just my basic genetic code. Same goes for YOU, or anyone else.

Very great perspective