The Weekender: Witch hunts, Vincent Price, and a cat fight of epic proportions

What we’re reading, watching, and listening to this week

Halloween is just a few days away, which might explain the spooky note humming throughout this week’s selections. A charming picture book about cats contains a scene of strongly implied cat-on-cat cannibalism. An eerie coincidence arises in the latest manifestation of the literary world’s obsession with Joan Didion. An essay explores why the invention of the printing press could be responsible for medieval witch hunts. So why fight the inevitable? We round out the issue with a clip from a classic horror movie, a short story about a monster, and a recipe for pumpkin chocolate chip cookies. Enjoy.

NATURE

Moonstruck

What starts as a school project to record the moon’s shifting phases becomes a treasured ritual between Jacqueline Dooley and her daughters—even, and especially, after Jacqueline loses her eldest.

14 Years of Writing About the October Moon

—

inOctober 1, 2010 | 3:30 pm | Last Quarter Phase

My daughter arrives home from school with a slim notebook covered with photos that represent the night—owls, a gibbous moon cut from white paper, a riot of stars.

She’s pasted the letters of her name (cut from the pages of a magazine) above the chaos of images. It looks a bit like a ransom note.

“A NA”

“What’s this, sweetie?” I ask.

She explains that she has a new 4th grade assignment. Starting on the 7th, which is the first day of the next moon cycle, she is to go outside, observe the moon, then write and draw her observations. She must do this every day throughout the month until the 31st.

I am delighted. I run upstairs to retrieve my own notebook—an empty journal with a blue butterfly on the cover. I anticipate (with great enthusiasm) sitting outside in the dark each and every evening for a month, looking up at the sky, and writing about the mysteries of the moon.

A week later, armed with pens, notebooks, and flashlights, we make our way outside after dark. Emily, my younger daughter, joins us. She’s six years old and can’t read or write very well, so she brings her crayons and draws the sky on blank printer paper.

October 7, 2010 | 7:41 pm | New Moon

“The night sky is very clear. lots of stars are popping out tonight. The new moon is impossible to see. The stars are very faint. I saw a planet too.” —Ana

Ana’s first entry, carefully printed in neat letters beneath a pencil sketch of the sky, is perfectly, childishly literal. She reads it to me when we are done writing and drawing, then asks me to read mine.

“There is no moon, so what’s new? The sky, scrubbed clean, is a wash of darkness sparkling with faint starlight (only an echo of the moon). This house looms, a monolith set in stark relief, all angles and sharpness against the open dark.” —Jackie

She asks me why I wrote about our house when I was supposed to write about the moon. I say that since there’s no moon out tonight, I decided to write about the house, which is big and white and reminds me of the moon.

She looks at the house, perhaps trying to make sense of how it can be like the moon. I tell her that, for me, the moon is only the starting point. It is a prompt to write about what we see and feel in the night.

SHORT STORY

PICTURE BOOKS

Cat fight

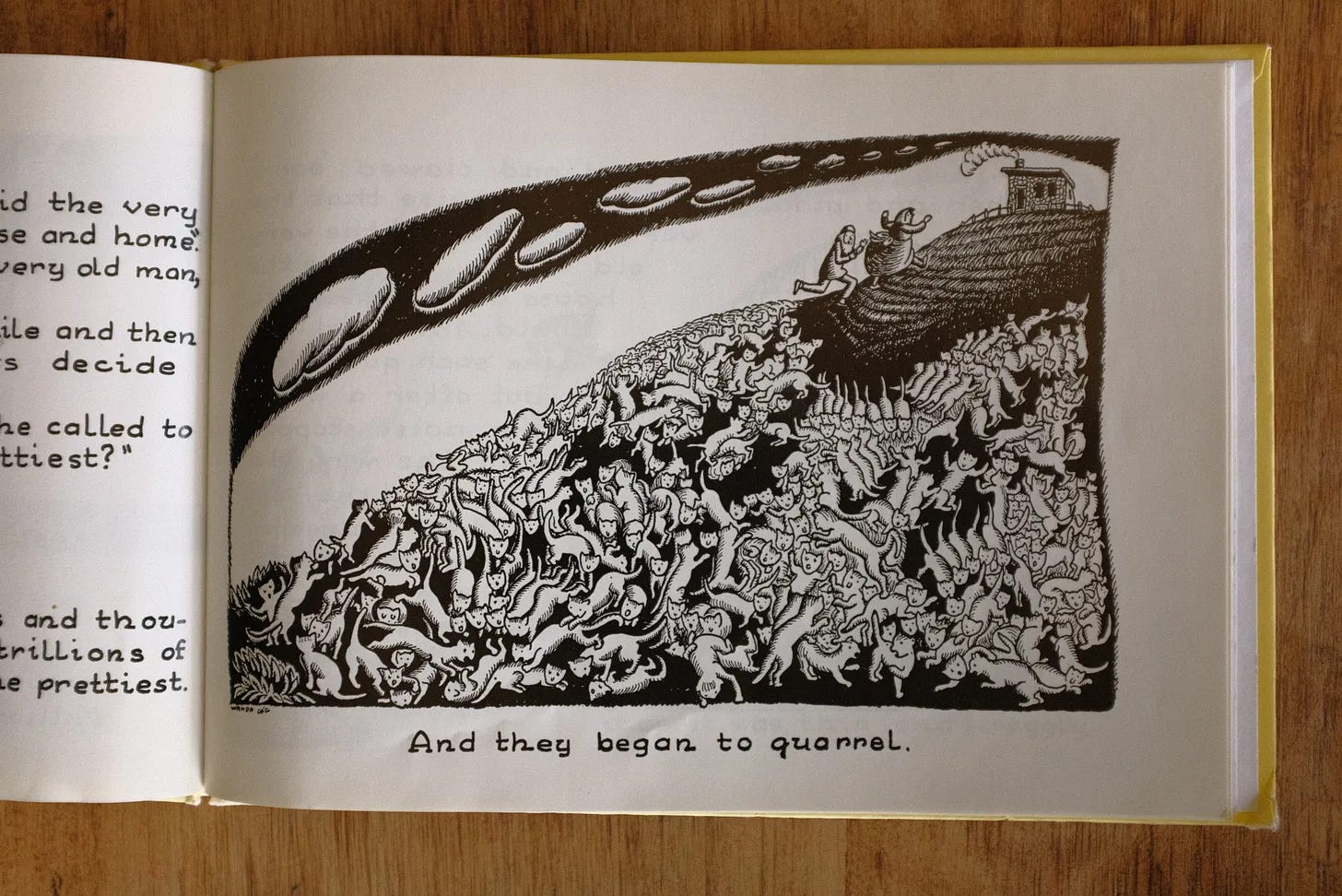

In their new Substack, award-winning children’s-book authors Jon Klassen and Mac Barnett analyze classic picture books, using their expertise to identify what makes great picture books tick. In this post, they discuss Wanda Gág’s Millions of Cats, from 1928, which originated much of what we now understand to be a picture book. They unpack a dark twist in the story: when the titular millions of cats turn on one another and “eat each other all up.”

Millions of Cats

—

and inMAC: The cat fight. A scene of incredible violence. This book kills off millions of cats.

JON: Billions of cats.

MAC: Trillions of cats.

It’s a very gruesome thing in a picture book.

So Wanda Gág has a new problem to solve: How do you draw a million cats killing each other?

JON: She doesn’t. She starts to. Gág is so good at picking only the most interesting moments to draw and letting the reader fill in the gaps between them. On this page the couple discusses the impossibility of caring for all these cats, but that’s not something any illustrator wants to draw or any reader wants to see drawn. Then the cats start to argue amongst themselves. Maybe a little more interesting. But really what the most interesting thing is [is] showing all of them just beginning to really fight. Like, just lunging for each other.

And she draws that. It’s a monumental thing to draw.

MAC: I agree that the fight is the most interesting, but I do want to linger on the arguing for one second.

Because this page, near the end, is the first time we learn that these cats can talk.

And we learn it because the man says, “Which one of you is the prettiest?”

And the cats start saying, “I am!”

It gives the story a folktale feel, but it’s a late revelation about the rules of this world that’s also just a really fun surprise.

JON: You could maybe argue that the cats can only understand each other. Like he might just be asking himself as much as them, but in their cat language, they all start to try and answer the question just for the group.

MAC: And look at the layout: It is a big illustration of absolute bedlam.

It looks like a Renaissance painting of hell.

JON: I even think the caption, placed where it is, recalls that. It’s captioned like a painting, with one line centered under the piece. It’s the only time she does that.

MAC: “And they began to quarrel.”

It’s a great juxtaposition.

The words fail to describe the enormity of the scene, millions of cats attacking each other. There’s a tension between the polite language and the chaos we see. The words fail to capture the “reality” shown in the illustrations. That dynamic is one of the things that makes picture books so exciting.

ART

LITERATURE

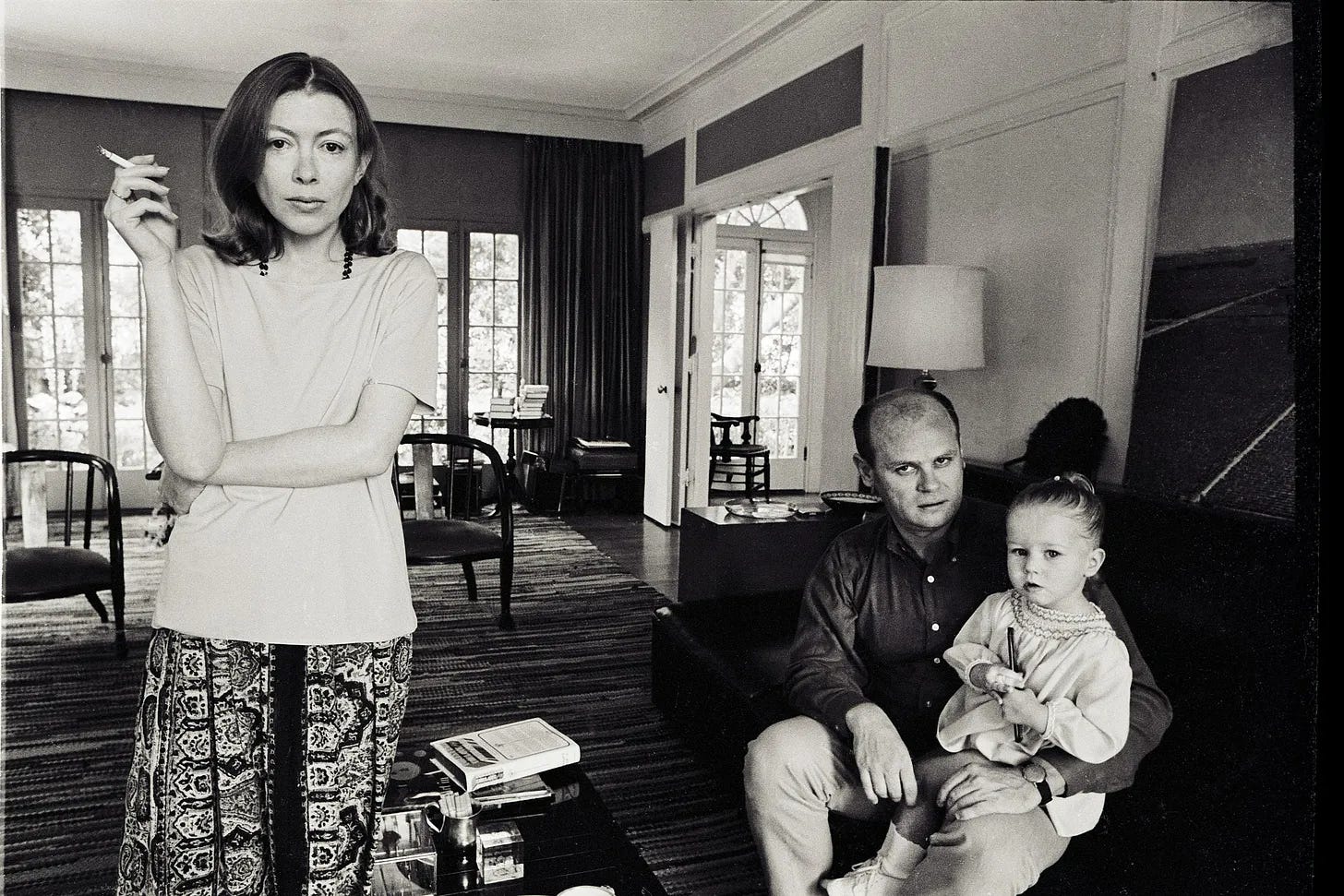

Everyone is reading Joan Didion right now

Call it The Month of Magical Substacking. (Or The Orange Album. Or Substack It as It Lays. Or Slouching Towards Substack. We could keep going, but we won’t.)

Someone somewhere is always reading Joan Didion. Someone somewhere is usually writing about reading Joan Didion. But it’s interesting to see several of Substack’s literary luminaries simultaneously grapple with one particular Joan Didion essay: “On Keeping a Notebook,” from the collection Slouching Towards Bethlehem.

summarizes the essay in her post about commonplace books in a quote directly from Didion, as she wonders why she bothers to record random observations: “In order to remember, of course, but exactly what was it I wanted to remember? How much of it actually happened? Did any of it? Why do I keep a notebook at all?” uses “On Keeping a Notebook” and her shifting irritation and identification with Didion’s writing as a premise to interrogate the concept of “butthurt” and how it affects the way we interpret literature—eventually realizing that the butthurt she feels while reading Didion may well be the same butthurt younger readers feel when reading her own novel The Idiot. opens her post exploring the desire to craft narrative throughlines in our lives and relationships with a quote from the essay:Perhaps it never did snow that August in Vermont; perhaps there never were flurries in the night wind, and maybe no one else felt the ground hardening and summer already dead even as we pretended to bask in it, but that was how it felt to me, and it might as well have snowed, could have snowed, did snow.

If there are any theories as to why “On Keeping a Notebook” has permeated the cultural psyche so suddenly, please let us know in the comments.

More in Didiontober:

- on why Joan Didion was “petty as all hell,” and why that’s what makes her so great: Cranky Joan Didion holds a grudge

- on breaking the vise grip Joan Didion’s voice holds over young female writers: I don’t want to be Joan Didion

- on failing to connect with a bookstore employee over a love of Joan: A bookstore, joan didion, and me

PHOTOGRAPHY

HISTORY

On witches and writing

Throughout much of European history, wise, skilled women were widely accepted and respected by their communities. Then came the medieval witch trials. In this post, Katie Jgln reviews a study that ties the proliferation of witch hunts with the invention of the printing press, a new technology that allowed misogynistic ideas to spread like, well, fire.

How the Printing Press Ignited Europe’s Deadly Witch-Hunt Frenzy

—

inThe printing press originated in China and was invented by a man named Bi Sheng. But, thanks to historical bias in favour of the West, you’re probably more familiar with Johannes Gutenberg, the German goldsmith credited with creating the first modern printing press around 1440 CE.

And it was Gutenberg’s invention that played a significant role in Europe in the centuries that followed, enabling ideas, news, and knowledge to be shared far and wide, which then contributed to the spread of education, literacy, and, as many argue, the Renaissance.

But it also helped to spread something else: prejudice, social polarisation, and even violence. In particular, against women.

Now, it’s true that some early Christian church fathers, like Saint Ambrose and Saint Augustine, began to look at women who had even a little bit of power, knowledge, or pagan audacity — female healers, midwives, herbalists, etc. — with growing suspicion from around the 4th century CE. But their ideas weren’t exactly quick to spread. Most people were illiterate, religious sermons were delivered in Latin, and written works — also frequently in Latin — weren’t easily accessible to the general public.

Luckily for some, and very unluckily for tens of thousands soon accused of being ‘witches’, Gutenberg’s machine arrived just as these ideas took a dark turn. Malleus Maleficarum (‘Hammer of the Witches’), possibly the most misogynist text ever written, was published in 1486 — right when the first printing shops were spreading across Europe. Written by two Dominican priests, the text served as a witch-hunting manual, its title not so subtly signalling its purpose: enforcing Exodus 22:18, ‘You shall not permit a sorceress to live.’

Unfortunately, it was hardly the only text encouraging people to identify, interrogate, and prosecute those believed to be in league with the devil. The popular press quickly hopped on the trend too, churning out countless one-page pamphlets and broadsheets — the precursors of modern newspapers — devoted to sensationalist ‘news’ stories of women flying on oven forks, burning towns, and eating children. These were often accompanied by exaggerated, brightly coloured illustrations featuring topless ‘witches’ and equally attention-grabbing headlines, which historian Natalie Grace once described as ‘the early modern equivalent of clickbait.’ The stories themselves were also essentially the modern equivalent of fake news.

Still, they were popular with the general population and highly profitable for the booming printing industry. So what’s the harm, right?

Well, according to a recent study published in Theory and Society, the printing of texts about witchcraft and witch-hunting, particularly the Malleus Maleficarum, played a crucial role in spreading the persecution of women suspected of witchcraft across Europe. After analysing data from 553 cities in Central Europe between 1400 and 1679, the researchers observed a significant increase in both the frequency and intensity of witch trials following the publication of each new edition of the Malleus Maleficarum and other similar texts.

PHOTOGRAPHY

FILM

A horror classic

Please enjoy this clip from The House on Haunted Hill, in which Vincent Price says the word “amusing” more iconically than anyone before or since.

The House on Haunted Hill

—

inTRAVEL

Gator tales

In what feels like a quintessential Lana Del Rey move, she recently married a swamp tour guide in Louisiana. In this post, Ock Sportello agrees to take his parents on a swamp tour and, naturally, chooses the one hosted by the new Mr. Del Rey’s (former?) employers. There’s no sighting of the happy couple, but he does get up close and personal with a different swamp celebrity.

Did You Know That There’s an Airboat Tour in Des Allemands, Louisiana

—

inMost swamp tours, you see, are what Chad calls “marshmallow tours.” The concept’s simple: you’re not supposed to feed wild alligators. Alligators are naturally afraid of humans—when they see us, their instinct is to flee underwater and to safety. Large-scale commercial tours attempt to coax gators out by throwing marshmallows into the water, which to a gator is something like one tenth of a Tic Tac. In Dufrene Swamp, however, the Matherne and Dufrene men keep their gators fed to the point that the alligators associate humans with food, the type of line you’d imagine hearing during the expository portion of a Jurassic Park sequel.

I should specify here that the Arthur’s Airboat friendship with the swamp’s gators appeared exclusive to the male gators. The female alligators are decidedly less friendly, likely owing to the fact that we spent the first fifteen minutes in the swamp trying to abduct their children. Here, in essence, is the broad outline of your tour: five minutes idling through nature, ten minutes ripping through that nature, catching a baby alligator to feed and hold, then checking in with the big fellas. We struck out on our first pass at the babies—Chad took us to the spot he’d just raided, but he speculated that his father had scared the mother and her nest away. As he explained this, he walked barefoot on what he taught us was functionally floating marshland, which traversing requires something like the walk they do in Dune, insofar as you never know when your next step will have you plunging into the swamp full of mother gators who recognize you as the guy who steals their children so that people like me can hold them.

After moving on from our failed pursuit, we crawled through the mesmerizing swamp. We marveled at local birds, which reduce well in a gumbo and which can be more freely hunted than ducks due to their number and their general stupidity. We got momentarily stuck in one of those floating marshes, requiring us to wait it out until the marsh sank. Then, out of the corner of his eye, Chad spotted Pierre.

You can tell the size of an alligator by the length between the end of his nose and his eyes, every inch of distance being roughly one foot of size on the gator. Chad joked that men often overestimated the size of alligators, but I’d like to think something other than penis envy was at work when I say that Pierre seemed a lot bigger than 10 feet. Chad called Pierre closer and closer to the side of the boat that my mother and girlfriend occupied; “Mange, Pierre,” he drawled. Before long, Pierre had brought his front leg and his entire head onto our relatively small airboat as Chad dangled raw chicken over his snapping head.

The experience of Pierre on the boat is one that doesn’t really lend itself to words. You really have to try it for yourself—if I haven't yet made it abundantly clear, you really should go to Airboat Tours by Arthur if you find yourself in Louisiana, just don’t be weird about it. As Pierre, the gigantic alligator who associates humans with food, basically walked onto our boat, I was so impressed by the absurdity of the situation that I couldn’t really find fear to hold onto. My mother, who was pretty reluctant in the first place, sat in what I could only imagine was a state of paralysis. But the more Chad patted, pushed, and finally kissed Pierre’s snout, the more he started to resemble a smiling dog. Before long, he felt like a lifelong pet. I wanted to kiss him too.

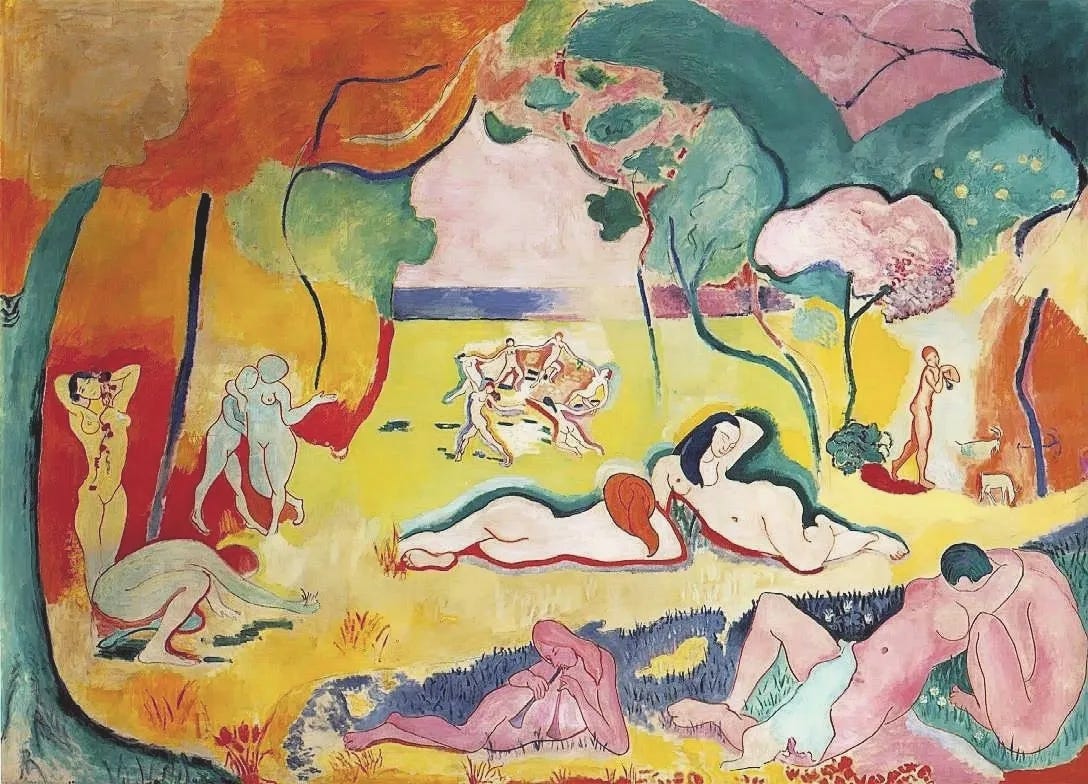

PAINTING

FOOD

Pumpkins, pumpkins, all around

This quick, easy recipe is an ideal dessert to throw together before a Halloween party. Eric King shares his riff on a “viral”—and shockingly forgiving—recipe by Maya Kosoff.

Pumpkin Chocolate Chip Cookies

—

inI love a recipe that starts with “Combine all ingredients in bowl.” (How many of your family recipes start like that?) But their simplicity belies their power—plush, bright orange and actually pumpkin-y tasting, which is a feat since pumpkin is so bland. They break one of my cardinal rules of chewy cookies: avoid water—and there’s a ton of water in puréed pumpkin. But since this is a cake-y cookie, we’re not so worried about that, and that moisture contributes to a plush, tender crumb.

These cookies have to be up there with one of the shortest recipes I’ve ever filmed for social media—maybe five minutes to make the batter? They will be my go-to for a last-minute offering for fall occasions to which I’m already running late. And everything goes down with one bowl, few other dishes, and ingredients you probably have in your house right now. Plus, all the measurements are easily remembered numbers with few fractions—and it uses a whole can of pumpkin and a whole bag of chocolate chips! Let’s celebrate that!

The first time I tried my hand at making them I thought, Mmm, these are pretty good! And then I realized I fully left out the butter. (These gaffes happen more often than you might think!) They were actually not bad that way, in case you were wondering! “The recipe is truly so forgiving,” Maya says. “It can be made vegan easily, either by omitting butter by accident or subbing for a vegan alt, and it tastes the same.”

ADVICE

Substackers featured in this edition

Art & Photography:

, , , , ,Video & Audio:

Writing:

, , , , , , , , , , , ,Recently launched

Inspired by the writers featured in Substack Reads? Creating your own Substack is just a few clicks away:

Substack Reads is a weekly roundup of writing, ideas, art, video, and audio from the world of Substack. Posts are recommended by staff and readers, and curated and edited by Substack’s editors.

Got a Substack post to recommend? Tell us about it in the comments.

Thanks for including us :=

Vincent Price saying 'Amusing' is going to be playing in my head the rest of the day and I ain't mad.