Hot peppers, new fences, and drinking from wild water

Bill Davison recommends a few of his favorite Substack posts

This week’s edition of Substack Reads was curated by , who shares essays about the natural world, tips to re-wild your yard, and wildlife photography on his Substack, . Bill served in the Army and has worked as a biologist and organic vegetable farmer. He lives in Illinois with his wife and two children and currently works at the Savanna Institute, helping farmers grow trees and shrubs as crops. Some of his most popular posts are “What an Owl Knows,” “A Trusting Goldfinch,” and “Birds Are the Most Interesting Thing.” If you enjoy Bill’s edit today, be sure to subscribe to his Substack.

I have been a writer at heart my whole life. Now, at 53, I am beginning to realize my latent potential.

If you looked at my life trajectory, you would not predict it would lead to writing on Substack about nature, birds, gardening, and embracing healthy masculinity. My career largely entailed being physically active outdoors, and my identity was wrapped up in my accomplishments. It took a crisis to open me to the mysteries of creativity. A noisy career spent surrounded by mortar rounds, chainsaws, guns, and motors caught up with me when I developed tinnitus in 2018. After the sudden onset of this ailment, I began the long, slow, and often painful process of becoming more sensitive, letting my ego fade into the background, and opening myself to new ideas and experiences.

With this new mindset, I started writing. At the same time, I was learning to take photos of birds, and the creativity that was emerging in my writing spilled over into my photography. I realized I could use my knowledge of birds to capture compelling images and highlight intimate moments in their lives. The resulting essays often left me wondering, “Where did this come from?” People urged me to write more, and that led me to Substack.

Joining Substack felt like coming home to a family of kindred spirits. I found it incredibly reassuring and inspiring. Through Substack, I came to love poetry, and my writing has led me to new people despite my introverted tendencies.

I spent the first 48 years of my life conforming to the dictates of culture. I am less constrained now. I am moving out of a rigid, tangible, and concrete way of being into a flexible, intangible, and ineffable way of being. I am more interested in a turn of phrase than another turn of the crank. Writing has helped me realize who I am at my core and that, like all of us, I have gifts to give. Gifts that are elevated by the stream of poetic ideas that flow through the world like a soft breeze and buoy our best intentions. We are in this together, and we can all take flight and realize our potential by following our inner light.

Here’s to shining more light into the world by supporting writers who are open to epiphany. They can connect us with life outside of ourselves so we can move out of our heads and into our hearts.

RURAL LIFE

The Field

—

inIt’s the rare author who can so vividly describe a scene that you can feel the damp air and smell the sea. David Knowles is one such writer. David is a fighter pilot and poet working on a PhD in Gaelic dialectology at Edinburgh University. In his essay “The Field,” he describes how he adapts to life in a small village after leaving the structure of the military behind. He finds that the company of a dog and a newly strung fence shape his life on the land. In the process, he comes to know the resilient residents who stay attached to their small plots of land, despite larger economic forces that pull them away. His writing is a joy to read.

Through the half-light of a northern winter morning, through a smudging rain that wets you from the inside out, through air saturated with the sound of the Atlantic swell, never resting, looms a fenceline. In the midst of a dereliction of fallen stone walls, corroded stumps of posts and needle-sharp rottings of old wire, there is this tight, new stretch of stock fence, the wire still shiny, the posts young and straight-backed, parading up the slope. Feel the tension of the wire. This fence will last fifteen years or so at attention and maybe a further ten at ease, I would guess, with a little fettling here and there, where it crosses the wetter ground.

RELIGION

New light: Finding universal truths

—Erik Rittenberry in

When I first dipped my toe into the ocean that is poetry, Poetic Outlaws by Erik Rittenberry became my immediate go-to. Every week, Poetic Outlaws delivers a thought-provoking poem and the occasional essay. I discovered Charles Bukowski here. What a gift! Erik is an excellent writer as well, and I enjoyed learning about his experiences with religion and how reading has helped shift his perspective over the course of his life.

I was brought up in the Baptist tradition from a very early age. Sweltering Sunday mornings in the south, a child I was, sitting in the cramped pews all dressed up, listening to the preacher man tell me how to live and what to believe and the daunting consequences that await if I waver from the Word.

Throughout my youth, I was taught to think of God as some omnipotent “entity” that we all are commanded to “believe” in. Or else.

The scriptures were taught to me through a literal lens. The mysteries of the divine were never entertained. It was all factual, exact, and unquestionable.

But in due time, my relentless curiosity and passion for reading helped me sift through the layers of my conditioning. Books have been instrumental in evolving my thoughts beyond the constricted viewpoints and moth-eaten doctrines that were force-fed to me on Sunday mornings.

PHOTOGRAPHY

Been a little lost

—

inI have found a kindred spirit in David Perry. We are both pulled to capture (or attempt to capture) the beauty of nature and the essence of wild creatures with our cameras. Then we process our thoughts and feelings about these images into essays. So for me, reading David’s work is like having a meaningful conversation with a close friend. He has an equal talent for writing and photography. He manages to blend beautiful prose with a conversational tone. And you’ll want to go back to his photos again and again to appreciate his eye for composition, light, and color.

I loved this recent essay about how we can feel lost at times and find our footing again by connecting with nature.

One of the ways I do this is to make pictures: deliberate, aesthetically framed observations, a kind of meditation, a journal. I listen to bird songs. Pick up rocks whose energy speaks (or sometimes merely whispers). I sniff the wind, take off my shoes, bury my feet in the sand or wade in the muddy shallows. I swim in the river’s big eddies, taste the fruits hanging from nearby branches, crush leaves and breathe in their scents. I drop to my hands and knees, lift up the bedspread and say “Boo” to the monster that it turns out isn’t actually hiding under the bed after all.

GROWTH

Hot peppers and radical acceptance

—

inSuleika Jaouad is a cancer survivor who practices self-acceptance to help her embrace the small joys in life. In this essay, dogs, peppers, and family help her navigate uncertainty. She describes why her life is good despite her illness, and might even be good because of it, thanks to the clarifying power illness can bring. Her lucidity enables her to plant the seeds of future joy amid the challenges of the present.

I’ve been thinking recently that the people I admire most are not those who bend reality to their will, but who accept it and find creative ways to engage with it. I think that’s my definition of resilience: to accept what’s happening moment to moment, and to allow for necessary adjustments, to pivot, to find relief, to cultivate small joys. And in that same vein, I try to plant seeds for future joys, for things to look forward to—like next weekend, when our tabasco peppers will be ripe for the picking.

CLIMATE

Putting hands to work

—

inAs a Midwesterner visiting the coast of Maine in 2015, I felt like I’d entered an otherworldly place. The ocean’s vastness, the deep and mossy woods, the lobsters. Nothing about it was familiar, and everything about it was magical.

Jason Anthony comes from a long line of Mainers living on the Atlantic coast. He also spent quite a bit of time in Antarctica. I suspect this explains his commitment to sharing his in-depth knowledge of climate change, which he does with a poetic sensibility. His essays are edifying and inspirational. He can tell you about the impact of roads on wildlife, the mystery of eel migration, and how to build birdhouses. Jason doesn’t just want you to understand the problems associated with climate change; he wants to empower you to be part of the solution.

Just as nature is not contained in the word “biodiversity,” the Earth is not contained within a map, globe, or satellite image. Society cannot be found online. Your photo is not you. We know but forget that the richness of reality is hidden in shadows as we navigate our busy days, moment by moment, through a muddled world of makeshift representations, whether digital, physical, or aural. I think of it as the human theater.

This online essay is representations within representation, coding and pixels forming words, which, lest we forget, are mere sounds or scribbles we’ve agreed to endow with specific meanings. Words are currency within the information economy, but like coins or bills (or the idiocy of crypto), they are only social constructs.

We are social apes in a world of stone, ocean, fire, air, soil, microbes, insects, plants, and animals. We’re only a part of the biodiversity. In fact, we’re nothing without the community of life. But we live in an era in which a few centuries of destructive human behavior have made any discussion of biodiversity a depiction of lives being lost, of the diminishment of solitary bees, pangolins, hemlock trees, forest elephants, right whales, prairie grass, and millions more.

All of which is to say that it’s vital for us to step out of the human theater whenever we can and put our hands to work saving plants and animals that are right in front of us. We desperately need the connection, and they desperately need us to reconnect.

NATURE

Soil and soul, water and light

—

inI was fortunate to live in Missoula, Montana, during my undergrad years. When I ran across Antonia Malchick’s Substack, I found that her way with words matches the beauty of the northwestern Montana landscape she calls home. Antonia has a deep appreciation for walking in the outdoors. In her essays, she examines how our relationship with the land has shifted over time, particularly in regard to “ownership, private property, and what we lose in the privatization of the commons.” It’s personal for Antonia, as she watches more acres come under private control and communities lose access to the land and water.

I don’t drink wild water frequently anymore, but driving up to this most recent camping trip at one of my favorite river spots, I had an incredible thirst. I didn’t want books or food, and definitely not other people. Just cold, clear water. I set up my tent, chopped some firewood, took my shoes off in relief at the feel of evening-chilled dirt and dry pine needles, and went down to the river, where I found a hole deep enough to dunk in and some comfortable rocks to lie on afterward, warmed by late afternoon sun.

The taste of the river lingered on my lips—snowmelt and sand, cutthroat trout, the huff of an elk herd I’d passed earlier, thousands of years of human relationship, ancient rocks tumbled smooth, the cold wild rose of the evening light, and a bit of iron that tasted something like resilience.

POETRY

I read a poem and now I’m pretentious

—

inNot all nature writing has to be about beauty, poetry, and close encounters with wildlife. Sometimes, as with Hari Berrow, nature writing is about … complaining. Hari describes herself as someone who loves nature but is pretty sure that nature does not love her back. Her first essay, “How I will learn to stop worrying (and love outside),” made me laugh out loud. She is prone to sunburns, migraines, and bug bites, but still attempts to get that transcendent outdoor experience others talk about. Although her primary tone is humor—and she is very funny—Hari also offers constructive insights and effectively weaves unexpected threads into a coherent narrative, as here, where she brings the beauty of poetry and nature together (without being pretentious).

This month, I have been thinking a lot about nature poetry. But not in an ostentatious way. I’m not conceited :)

I can’t pretend to understand poetry very well. I did English Literature A-Level (I got a B), and when I was teaching in the English department at the university, I taught some seminars on it. I’m a big fan of Terrance Hayes. I don’t really get it all, though, it seems just like prose but shorter and with weirder ways of saying things. But, I will say this, it does something, doesn’t it? Poetry. It does something to your brain. Pokes a finger in and wiggles around inside it.

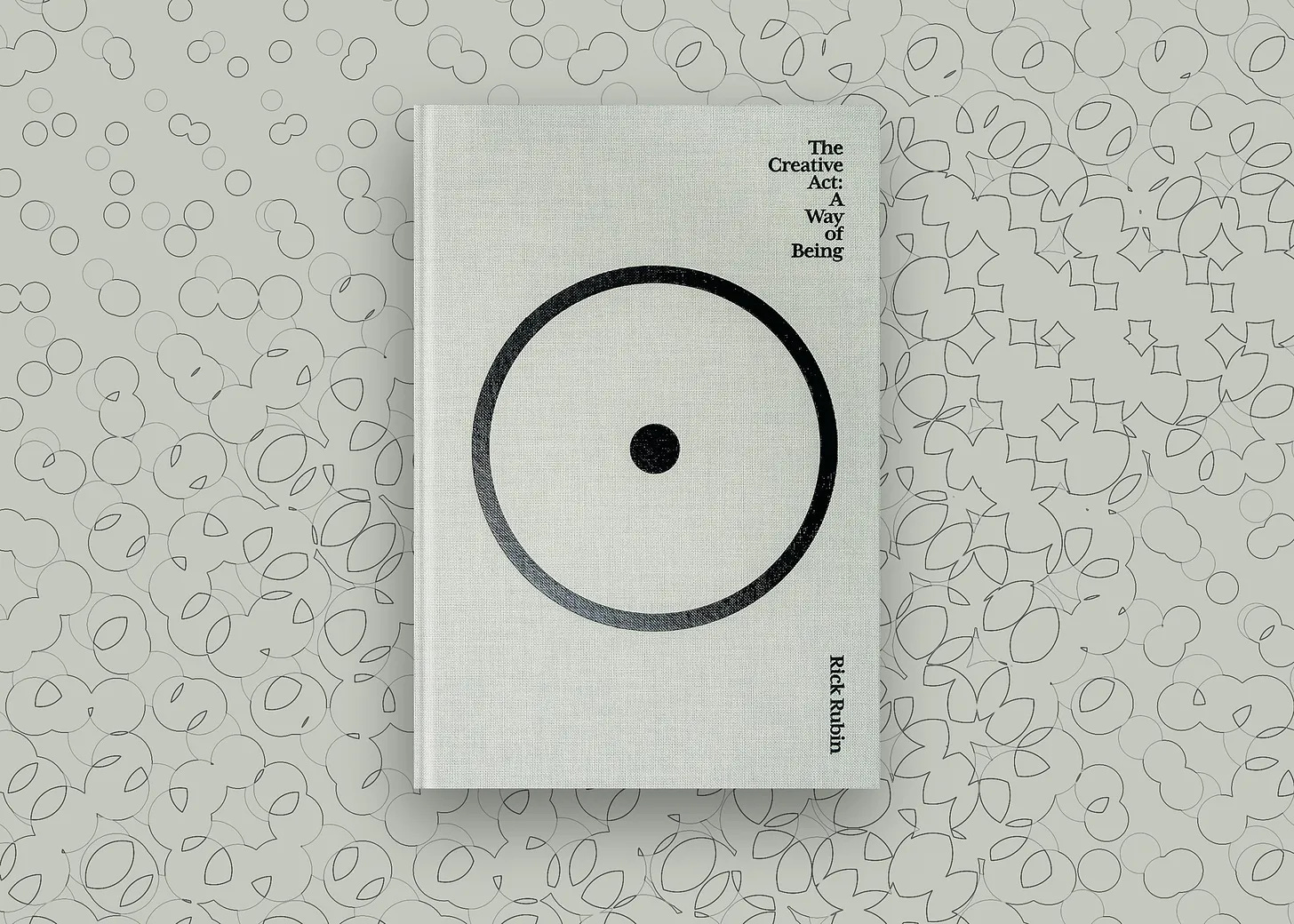

CREATIVITY

Art as a way of being

—

inPrior to reading Bill Sawalich’s Art + Math, I hadn’t given much thought to the work of a professional photojournalist. Their subjects tend to be dismal: headline news (dreadful), sports (I’ll pass), and celebrities (don’t get me started). It all seems so distant from what I’m trying to accomplish. But I was wrong! Bill’s snappy and articulate writing style, along with his years of experience in the world of photojournalism, showed me that all creative people face the same challenges and criticisms—even when they’re as famous as Rick Rubin.

While reading Rubin’s book The Creative Act: A Way of Being, Sawalich finds freedom in the concept that following the rules leads to average art.

I know the way things should be done, and so too often I put the “how” ahead of the “why.” When you have been trained as a craftsperson, it’s too easy to fall into the trap of technical excellence equating to artistic excellence. This is evidenced by the technically simple paintings and photographs that have long garnered exclamations of “I could paint that!” It can be exceptionally difficult to set aside technique in an effort to focus on something even more essential.

Case in point: For years I operated as a photographer as if there was a “correct” exposure for every shot. Meaning, no matter how much I worked to ensure an image was neither too light nor too dark, too warm or too cool, I lived in perpetual fear that some expert would come along and say “that’s too dark and too blue.” Imposter syndrome, sure, in part the fear that I’d be found out. But more than that, it was a failing in my thinking about something as fundamental as photographic exposure. There’s no such thing as “correct,” of course. There’s only the mark I choose to put on the paper (or pixels). Photography is painting, poetry is pottery. If Picasso can break all the rules, so can we. In fact, so should we.

New on Substack

This week we released Substack Summer Recaps, an at-a-glance, personalized recap of everything you read, watched, and listened to in the past few months.

shared a lovely reflection on her Recap in and discussed why reading on Substack is her favorite thing to do: “Brilliant writing, from my favorite writers, sent directly to my inbox — and I get to pay them directly, too.”Get your Summer Recap at the link below:

Reading this on an Android? Click here to get your recap.

Recently launched

Noteworthy notes

Inspired by the writers featured in Substack Reads? Creating your own Substack is just a few clicks away:

Substack Reads is a weekly roundup of writing, ideas, art, and audio from the world of Substack. Posts are recommended by staff and readers, and curated and edited by Substack’s editors.

Got a Substack post to recommend? Tell us about it in the comments.

Hooray! Delighted to see Bill featured here - and Antonia as one of his recommendations! Both doing terrific, enormously heartfelt work on Substack so I hope a ton of new readers for them is the result of all this.

This is probably my favourite Substack reads edition so far. It's so much in line with the spirit that I want to cultivate on this platform as a writer. A contemplative Saturday read that reminds us of the simple but beautiful things in life.