Cormac McCarthy’s secret muse, the internet, and me

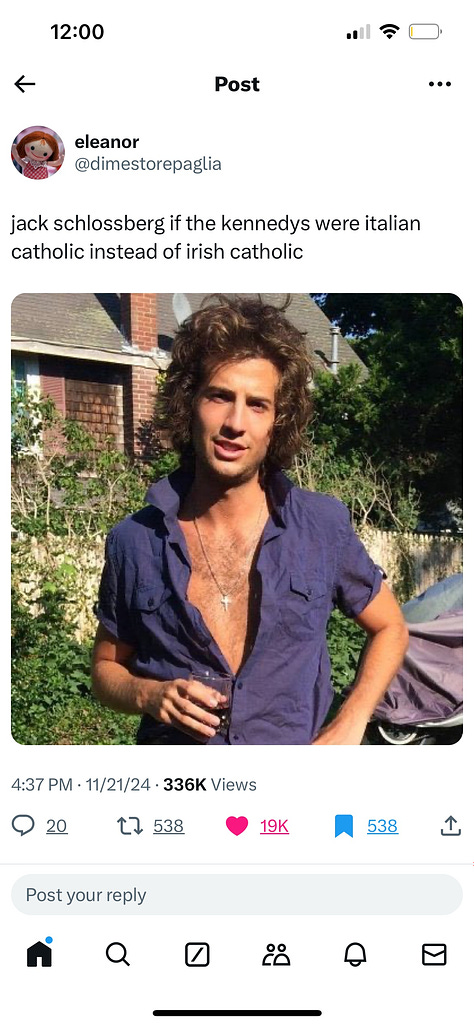

Vincenzo Barney on making a life-changing connection in the comments section

There’s a curious resonance between writers and the names of their first biographers. Proust, for instance, twinkles in the eye of his infatuate Painter. Nabokov playfully outfoxes and hides in his Field. Larkin is blurred in Motion. Bellow wobbles blandly on his shrugging Atlas. Amis is led astray by his Leader. Inaccuracies persist by the dozen in Hemingway’s Baker. Now, I am no biographer, but as they say in the U.K., Cormac McCarthy and Augusta Britt (the most significant muse in American literary history) got into a bit of a Barney last month, thanks to a profile I wrote for Vanity Fair.

I had done the unconscionable thing of telling the story of Augusta Britt and Cormac McCarthy’s half-a-century relationship—which inspired several famous novels and characters—from Augusta’s own perspective and in my own style. It went viral, becoming Vanity Fair’s second-most-read story of 2024. The response was just what a debut writer dreams of reading: it was suggested I be jailed. More than one online bystander paid me the courtesy of writing in private to say that, really, the honorable thing would be to end my life, and provided several helpful scenarios and detailed how-to’s on how this could be pulled off. Meanwhile, those more diplomatic of heart suggested a petition merely be circulated, barring me from ever writing or publishing again.

But here I am, writing again. And once more, it’s all Substack’s fault.

In the autumn of 2022, Cormac McCarthy’s final novels, The Passenger and Stella Maris, were released months apart in a dyad. (Now, dyad’s the type of word I used in Vanity Fair that really got under the skin of people who purportedly love language. Modern decorum requires a prose so frictionless as to be nearly indistinguishable from having read anything at all. And that’ll be the next critical innovation: not reading at all. But here I am, swelling up a pair of parentheses, another taboo!) Nobody knew McCarthy’s writing better than me, according to me. So with only a 500-word Air Mail credit to my name, I humbly wrote to several magazines, journals, and literary and culture sites. “Let me procure an advance copy and review these novels. You can’t go wrong.” No one responded. It all went wrong. It was almost as if a petition had gone round barring me from… Anyway, not being anyone’s charming nephew but having met writer

(who runs a great Substack called ) and been encouraged by her to take matters into my own hands, I decided to take matters into my own hands. I created my Substack, .I waited patiently for McCarthy’s novels to find their way to Barnes & Noble and began to write my review. A 10,000-word essay, really, that indulges Cormac McCarthy’s entire oeuvre—I word I don’t disagree is pretentious—and assesses his final novels from within it. I wrote it on nights and lunch breaks and weekends between my day job, and it took me months, through the holidays, through the beginnings of spring.

On March 31st, I decided my essay, “Cormac McCarthy Stumps in Florida,” could be no more improved upon nor tweaked by me and my indefatigable red pen. On April 1st, I put my last images and links in place and published it. To my shock, my essay actually got some attention and won me about one hundred subscribers over the course of a month—many of them from Substack’s own recommendation engine. I learned that there really was a vibrant community here, one that was shockingly interested in reading essays containing words like “dyad.”

That night I received a comment on my essay of such cryptic honesty and artistic enigmatism, it could only have been written by someone very well read and with intimate knowledge of McCarthy. It was written to me in staves:

Santa Fe killed the Cormac I knew.

He gained fame, wealth and fancy superficial friends.

He turned his back on his old friends like Jimmy Long (J-Bone) and Billy Kidwell. They were left to die, forgotten and alone.

He lost much of his compassion and kindness.

As the Institute crowd claimed more of his time, he struggled to write. Couldn’t write. How could he? He’d stifled or killed that which inspired him.

The advance for The Passenger was spent. He was obligated.

These last many years he has taken up drinking again.

Living in majestic splendor but enjoying none of it.

Surrounded by junk and the clutter of a lifetime.

Haunted.

Crippled, embittered and alone. K— can’t be bothered to visit. Impeded perhaps by the reminder that he too will wither and die.

[...]

One day more light will be shed on the person Bob Coles described as Cormac’s Muse. His letters to her are still out there.

The formulation of these sentences was so literary, the syntax so McCarthyan. “These last many years he has taken up drinking again” sounds like the opening of some anti-Blood Meridian: “See the old man. He is pale and thin, he wears a thin and ragged linen shirt. He stokes the scullery fire… These last many years he has taken up drinking again.”

A game of cat and mouse ensued, with me trying to learn more about the commenter. It still being April 1st, I responded with something utterly foolish: “I’m very sorry to hear this about Cormac. It sounds like you know him.”

Days went by. I responded again, and another, even more cryptically detailed comment came:

It’s a sad and tragic end and one that Cormac hoped to avoid. It’s heartbreaking. He has been betrayed. Yes. I know Cormac. I met him when I was 16.

[...]

It was serendipitous that I found your Substack, it’s been oddly comforting and cathartic.

It was from Augusta Britt, the most consequential muse in American literature. Months later I would screenshot but delete these comments to protect Augusta’s privacy and to cover my tracks from other researchers—wisely, it would turn out, as several writers and biographers have tried in vain to get Augusta’s story from her over the last year.

When Cormac McCarthy passed away in June of 2023, I wrote an email to Augusta, offering her my condolences. (Yes, I thought up something much less boneheaded than “It sounds like you knew him.”) She wrote back and suggested we talk on the phone. The rest, as they say, is history. Moreover, I am too entertained by the internet speculation about what must have gone on between the lines, editorially, existentially, Augustally, to ruin the fun of anonymous critics. But I suppose I will pull back the curtain, only just.

We began talking on the phone every other night. It was summer by this point, so the day’s stage lights stayed lit until 7, 8 p.m. I sat on the porch of my family home with the phone to my ear as darkness descended, with all its dramatic, theatric possibilities. Covered in night grain, I sat listening as Augusta told me of her entire life. Her childhood, meeting Cormac at that motel pool, running off to Mexico. We connected instantly, we made each other double over in laughter, we shared our saddest, hardest moments. One night she missed a call. It was monsoon season and she’d been caught between two floods on a road out in “wildcat country.” I’d never been to Tucson, never been to the Southwest, so everything she told me excitingly strained my imaginative abilities. Her life adventures always featured epic weather or dramatic mountain ranges or those endless ocean-haunted deserts. My pen started to move across the pages of my notebook. Cormac appeared to me in a dream with his fingertips shining with light. I thought, “How do you not write All the Pretty Horses after meeting Augusta?” One day, she told me that she would never tell anyone else her story. “You carry the light,” she said. And so I carried it as best I could out to Tucson.

Augusta put such wild, beautiful images in my head that when I finally visited the Southwest, everything I saw was in her style. Her pull, her gravity, is just that strong. There is no one like her. I will never be able to thank her or repay her for entrusting me with her story and with over a year of her life. It has changed my own life forever.

My only regret in any of this is that Augusta has had to endure the worst of the online reactions, which was her greatest fear in going public: being misunderstood and not taken seriously. Many of the most viral public reactions on both social and legacy media immediately decentered Augusta from her own story, stripped her of agency, and then proceeded to take me to task for having respected her perspective on her relationship with Cormac McCarthy, whom she considers the most important person in her life. I consider the claim that an adult woman cannot be the authority on her own life to be contrary to the very ethos these critics claim to espouse: that a woman is the authority on her own life. Besides being a glaring hypocrisy, I find the violent expression of this contradiction (contradictions are often expressible only through violence and aggression) aimed at Augusta herself to be immoral. It is not surprising that the most self-valorizing attacks passing as thought were written on black rectangular mirrors we call smartphones when we aim them at our faces. Yes, today’s written discourse is propagated mostly by thumb wars, a child’s game. And it shows.

I have seen very little compassion or serious thinking. I have seen Augusta Britt’s dismissal out of hand—especially by those claiming to be outraged by what she had to “endure.” Everywhere but Substack, it would turn out, where many writers have published great pieces on it.

Anything I accomplish from here on out in my career, I owe and dedicate eternally to you, Augusta. And a lot of it will be done right here, on Substack.

Vincenzo, people are upset because you refuse to address the false claims you/Augusta made, which throw the veracity of your entire article into question. What makes it worse is that you're gatekeeping, manipulating, and hiding the real story/information to drive book sales for your book with Augusta, which I assume will double down on these false claims.

So, Vincenzo, I've asked you plenty of times, but are you ready to comment on the Guy Davenport letter? The one that Davenport wrote in 1974 about McCarthy

"Cormac McCarthy has just run off to Mexico with a teenage popsy, abandoning a beautiful British ballerina of a wife; somehow this negates all the critical thunder he boomed at Tatlin."(Questioning Minds, page 1,508)

So was Augusta 14 (instead of 16) when she went to Mexico with Cormac? Your article said they met in 1976. Or did Cormac habitually take young girls to Mexico (which would ruin your whole "Augusta is Cormac's Muse" angle)?

While discussing your false claims, are you willing to comment on the fake origin story you made up about Augusta meeting Cormac? The Orchard Keeper did not have an author photo on the back of the Ballantine paperback edition (the only paperback edition available during that time). In 1976 (or 1974??), when Augusta met Cormac, he had only sold 5,000 book copies. There was zero way in hell, an orphaned girl had come across one of those copies. And if she did, she wouldn't know what he looked like! So, did Cormac approach her???

If he did approach her, and we're going with your muse angle, are you willing to comment on your claim that Wanda is based on Augusta? McCarthy had written that scene into an early draft of Suttree over a decade before he met Augusta (when she was six or four, lmao)

Or how about your main claim that she inspired All the Pretty Horses? McCarthy had worked with John Cole on a movie set when he was a teenager and was indebted to him for getting him into film. When he wrote his screenplay in the mid-1970s, "Cities of the Plain," he named one of the characters John Grady Cole in honor of him. Not Augusta's fake stuffed animal named "John Grady Cole."

Do you have any proof she worked for Jim Anderson or in any way resembled Alicia Western?

Why have you personally tried to position yourself as an authority on Cormac and diminish scholar's work because you know Augusta by claiming McCarthy didn't know about Focualt or Gnosticism when I've read handwritten notes he's made about them? What about some of the other reaching claims you made on your recent Patreon Podcast?

Why would you do that other than to manipulate ethos for future book sales?

I could go on for days, Vincenzo, with more false claims, but stop playing the victim and start taking some accountability!

It is YOUR fault Augusta Britt is getting hated on. An hour of sitting on Google would lead you to all the information I stated above. You decided to publish the article (that you were paid for per word) without checking any information or at least telling the audience that her claims may be false.

You now have another paycheck coming down the pipeline with your new book with Augusta, and I assume we will hear nothing but silence from you about these claims because it would kill your potential to make money in the future.

I'm in the real streets of Tucson, and when you're ready to come down from the Catalina Foothills for an interview in the Escalade Cormac gifted Augusta, the literary renaissance will be waiting.

- The Cormac McCarthy Renegade Scholar Collective

Your VF article was amazing and sent me back to my bookshelves (yes, BOOKSHELVES) to reread McCarthy’s works with Augusta in mind. Fuck all the people who would deny her truth and words and tell us all how to rethink McCarthy and to erase him and his work—and Augusta. Thank you for writing this and the VF article. People out there in the blovisiphere should STFU.