“Being a fan of a losing team is, at its core, romantic”

In this edition of the Weekender: Apple Intelligence, the dangers of haggis, and a ghost story

This week, we’re considering the Super Bowl, having our texts summarized, buying Girl Scout cookies, and fearing a haggis invasion.

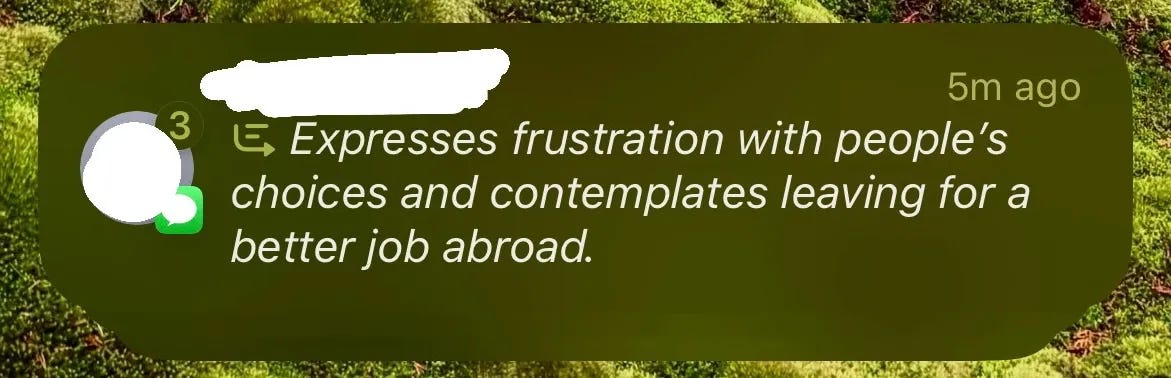

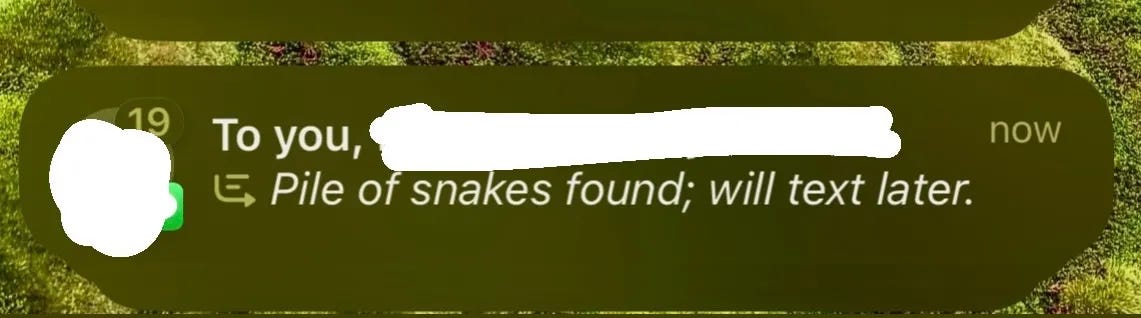

TECHNOLOGY

Updated

Delia Cai started receiving “‘Notification Summaries,’ wherein Apple Intelligence (A.I., ha ha, get it) condenses the content of my text messages into bulletpoint-esque takeaways.” Here, she reflects on what these summations say about how we communicate.

Eerie, clinical, and somewhat poetic

—

inWas it truly worth getting worked up about the latest way a tech company was inserting itself as a wafer-thin layer in between our interpersonal communications—and therefore, our human relationships? Didn’t the arrival of ChatGPT, if not the existence of the internet, already guarantee a future where my computer would talk to your computer to figure out what you and I want to eat for dinner, like a sub-class of Hollywood assistants promising each other whose people would reach out to whom? Still, it was undeniable that something was being lost, or rather, muffled in the plastic wrapping of these text summaries: Rather than checking my screen to see what my friends or my mother wanted to say directly to me, I was asking my computer to give me the highlights—the semantic essence, shorn of all the unnecessary context of linguistic quirks, inside jokes, and gorgeous wabi-sabi of my mother’s eternal war with AutoCorrect (another intrusion we have largely submitted to). These summaries made the experience of checking my phone feel denuded and clinical, which is probably another way of saying that it was a fully optimized experience, bro.

And yet there was an undeniable poetry, however unsettling, to some of it. I didn’t like the idea of a machine “reading” my private messages, but I did start thinking it was funny, over time, to see how these summaries were a sorting mechanism for the subtext of the original sentiments. By that I mean: While I (as a particularly text-based person) like to think the breadth of my message content (ew lol) regularly embodies the full spectrum of human thought and emotion, in reality it appears that all we are ever really doing is one of a few defined tasks: sharing, forgetting, inquiring, complaining, apologizing. How analog even those tasks feel compared to the true subtext of these interactions, which is, what? Seeking validation or extending care or simply affirming coexistence. In the future, perhaps Apple Intelligence will manage to boil it down further and eventually eliminate the gratuitous nuisance of forming sounds and symbols entirely. You’ll just be able to ping me straight in the brain, and I’ll know how you feel—assuming my iChip bill has been paid for the month.

ART

SPORTS

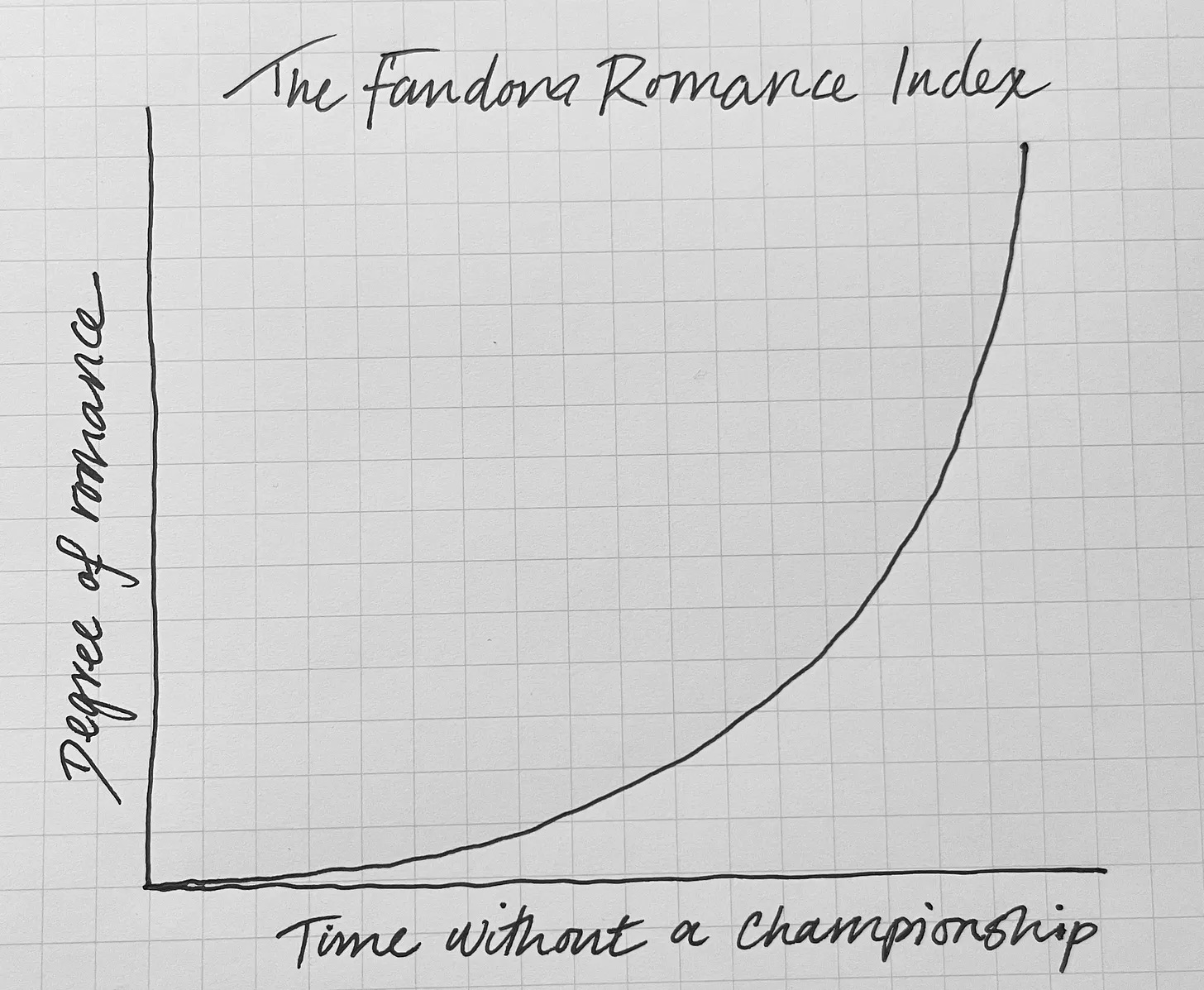

The beauty of losing

Ahead of the Super Bowl, Charlotte Wilder unpacks the romance of fandom, and the near-universal joy of hating a sports dynasty.

Sports dynasties are good

—

inAt the end of the day, your team probably won’t win a championship. It’s just statistically unlikely. Every league has many teams, and when the season is over, only one of them can win. It’s pretty cruel, actually. I get very excited for big games with high stakes—I love that sports are completely manufactured events that feel hugely consequential. When I report on championships in person, I feel like I’m at the center of the universe, and when I watch them on TV, I feel like I’m a part of a conversation that becomes a whole universe in and of itself.

And then I watch one team lose, and it really bums me out. When it’s my team that loses? The closest feeling I can equate it to is actual heartbreak. Breaking up with someone and watching your team lose elicit the same pangs in your left chest area, bring up the same feelings of “what if?”

But this is where the beauty of fandom comes into play: misery loves company. There are few things that make you feel closer to someone than commiserating over the fact that your team once again turned into a flaming pile of garbage at the end of a game. You say stuff to each other like “They should fire ____insert coach name here____ and hire me” (they definitely shouldn’t) and you both agree.

Being a fan of a losing team is, at its core, romantic. You love this thing that doesn’t really know you exist, will never love you back, is capable of bringing you intense joy and misery, and is usually loaded with nostalgia. The longer your team goes without winning a championship, the more romantic your fandom. Extra romance points if your team has recently gotten close and lost (Bills, Lions) or has just totally sucked for a very long time now (Jets).

[…]

So, as you watch the Super Bowl next weekend, your teeth clenched, your fists balled, your mouth yelling things like “The refs made sure the Chiefs would be in the Super Bowl,” remember that at least you’re feeling something. Something that can bring you closer to other people. Something that creates community. Something that, at the end of the day, doesn’t really matter at all and is all the better for it.

SKETCH

FOOD FOR THOUGHT

A dangerous proposition

Upon learning of a loophole that will allow haggis to be sold in the U.S., Dave Barry wonders what other “scary foreign foods” might be next.

The Haggis Menace

—

inThe first is lutefisk. This is a traditional Norwegian dish that I encountered in 1994, when I was in Norway covering the Winter Olympics. I organized an expeditionary group of courageous professional journalists on expense accounts willing to go with me to a restaurant in Lillehammer and attempt to eat lutefisk. Here are some excerpts from the column I wrote about that night:

Lutefisk (pronounced “lutefisk”) is the semiofficial national dish of Norway. This is somewhat ironic, because most people hate it. Even travel guidebooks, which always put the best possible spin on everything (“Between mortar rounds, Sarajevo offers the enterprising visitor much to...”) tend to describe lutefisk with words such as “repugnant.”

I asked a number of Norwegians what it was like, and the most complimentary response I got was: “It is very strong.”

The recipe for lutefisk basically consists of taking a codfish and soaking it in—I am not making this up—lye. I have no idea how this got started. You don’t think of lye as a common cooking ingredient (“Honey, could you run down to the 7-Eleven and pick me up a quart of lye?”).

The restaurant employees brought us our lutefisk almost as soon as we sat down, as though they wanted to get it out of the kitchen. It has a jelly-like texture and is served in quivering white slabs, which contain many bones. It has a distinct aroma. Not quite as distinct as wolf urine, but definitely headed in that direction. It is served with a little gravy boat filled with little pieces of crisp bacon floating in bacon grease. The idea is, you ladle a nice big glob of grease onto your lutefisk, and then, when nobody is looking, you sprint out of the restaurant and find a place that sells pizza.

No, that’s what we felt like doing, but instead we tasted the lutefisk, and we were pleasantly surprised. Some of the comments I wrote down were:

— “This is not totally terrible.”

— “I don’t hate this.”

— “It sort of slimes down your throat.”

— “I have eaten worse things.”

During the meal, our table was visited by the chef, whose name was Alf Johnny Eriksen (in Norway, “Alf Johnny” is the equivalent of “Billy Bob”).

“How do you like the lutefisk?” asked Alf Johnny.

“Best we’ve ever had!” we said. “Do many people order this?”

“No,” he said. “You are the first.”

I should clarify something: As far as I know, lutefisk is legal in the United States. But currently it’s confined to areas of the country with high concentrations of people of Norwegian descent, by which I mean North Dakota (population: eight). I worry that if we let the haggis industry gain a toehold, the lutefisk industry will make a move. Then we’ll be dealing with sheep organs and lye.

PHOTOGRAPHY

FICTION

Ghost story

BDM’s short story offers an arch twist on a terrifying premise.

A February ghost story

—

inShe saw them the first time she stepped through the door: the ex-girlfriends. They slid down the walls of his home, leaving trails of—what? ectoplasm, was that it?—behind them. They smiled at her with translucent gelatinous smiles. They were not jealous. They welcomed her as a sister. She was not jealous either—that was impossible, frankly, after all, they were dead and she was alive—but it was hard not to lift up her shoes with each step and shake them out, as if there were gummy traces of ex-girlfriend stuck onto the soles.

She let him take off her coat, hang it up, uncork the bottle of white wine she’d brought with her. It was plain she’d made the wrong choice, but he was going to be a good sport about it, even if the ex-girlfriends were not. He likes a nice Merlot, gurgled one of the ex-girlfriends, crawling down the refrigerator. You should remember that.

Really, said another, burbling at her feet, a white wine? Terrible choice.

One thing that was hard to ignore about the ex-girlfriends: they’d been chopped up. Their faces were split down the middle; their heads were barely attached to their necks; their arms would pop off their shoulders. She knew, then, though she would naturally have denied it. Did deny it, later, to the police. I had no idea (she would, did, say). No idea. She could hardly have said to them: I knew when I saw the ghosts.

Or maybe she could have said it. It wasn’t as if they really needed her to be a reliable witness: they’d found all the bodies. So she saw ghosts, so she was crazy—it didn’t make much of a difference when it came to the legalities. But it was bad enough to be a serial killer’s ex-girlfriend, you didn’t need to be a public lunatic, too.

And then, it was bad—it looked bad—if she knew and kept seeing him anyway. She was aware. That first night, in bed, their dead fish eyes watching from the walls, their clammy hands trying to guide her. She was aware. The glug-glug of their voices telling her what he liked, didn’t like. She was aware. She didn’t leave. It wasn’t like they’d be any less dead.

And anyway, they didn’t mind.

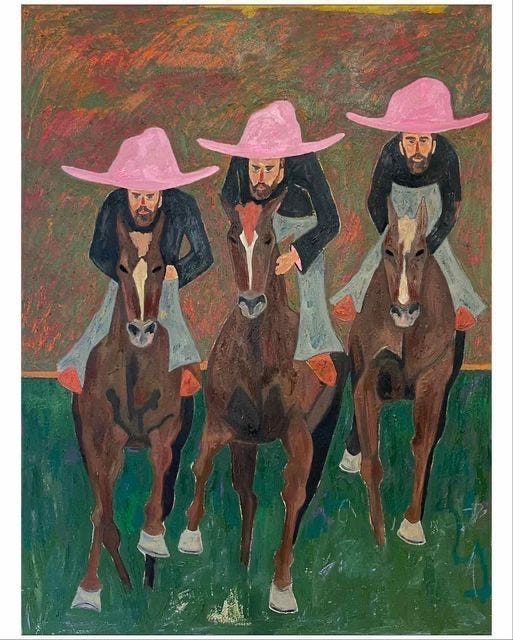

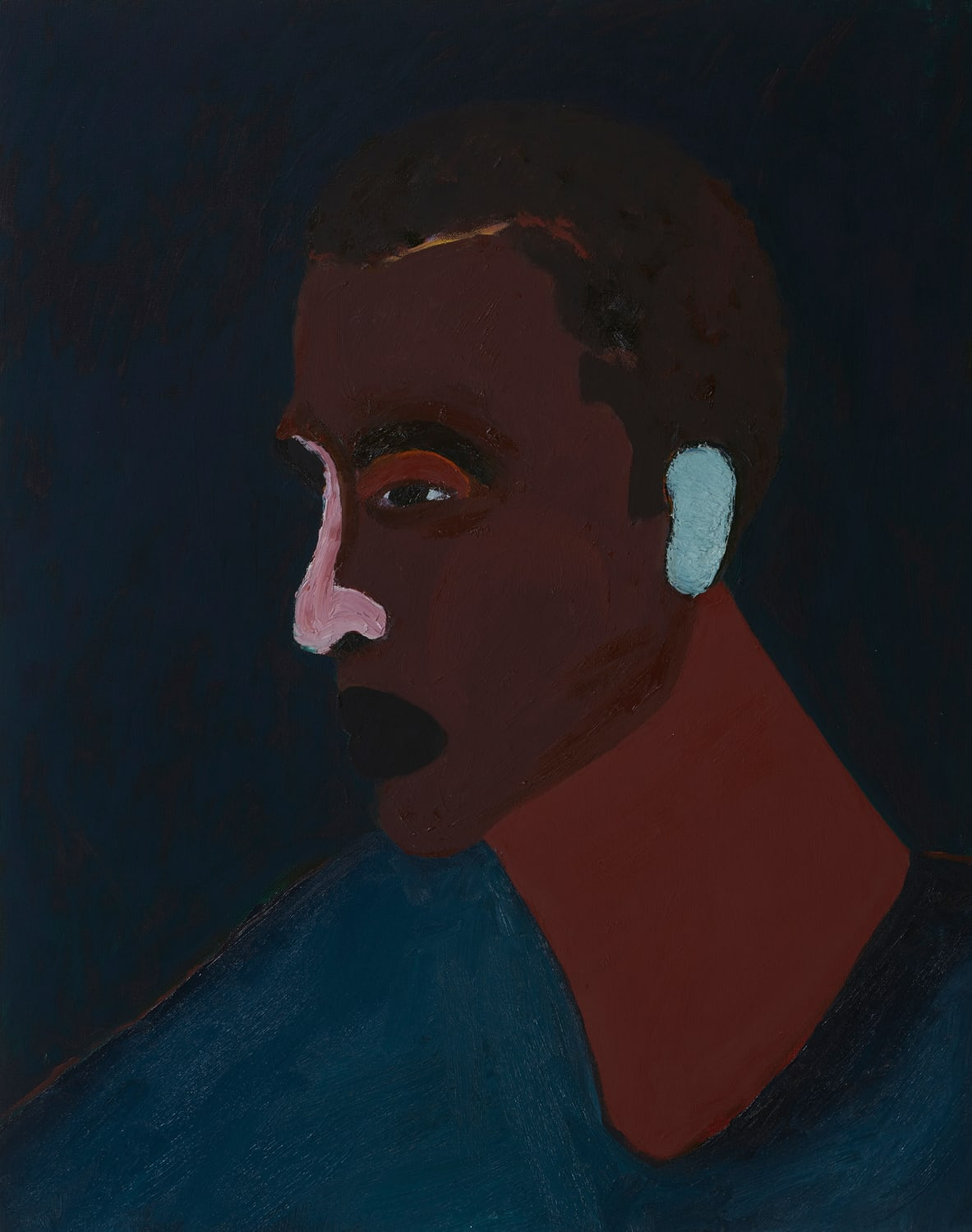

PAINTING

POETRY

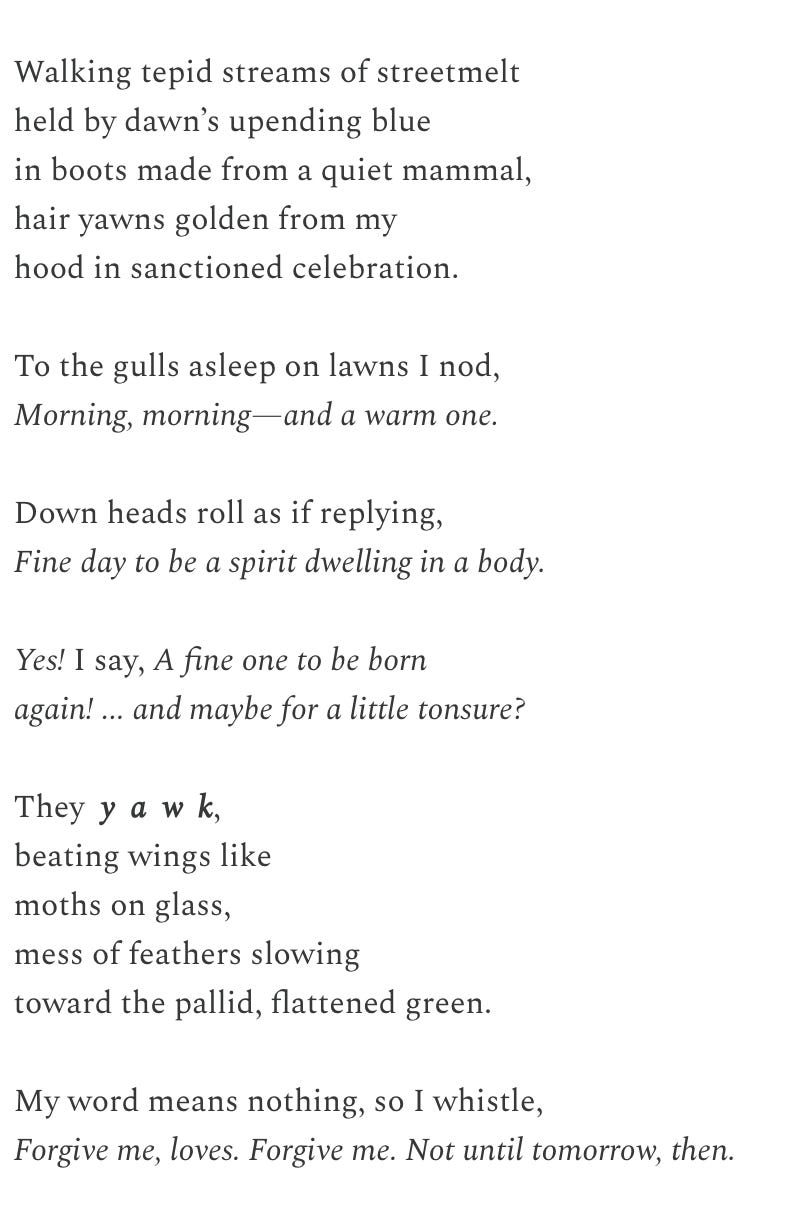

Tonsure

—

inPHOTOGRAPHY

FOOD

A dangerous season

Substackers featured in this edition

Art & Photography:

, , , Liz Magee, ,Video & Audio:

Writing:

, , , ,Recently launched

Inspired by the writers featured in the Weekender? Creating your own Substack is just a few clicks away:

The Weekender is a weekly roundup of writing, ideas, art, audio, and video from the world of Substack. Posts are recommended by staff and readers, and curated and edited by Alex Posey out of Substack’s headquarters in San Francisco.

Got a Substack post to recommend? Tell us about it in the comments.

I so appreciate that you include art in the substack. Sometimes words say too much and it is refreshing to relax and allow the imagination to be inspired. Thank you.

People who don't turn off auto correct shouldn't have a phone